I often end diagnostic interviews with leaders asking: “What do you worry about on the drive home?” Curiously, one answer pops up more than any other: “Something I don’t see coming.”

Is being blindsided part of the human condition? As social creatures, we get most of our opinions from those we already know. The Palin-Tea Party phenomena underscores people’s attraction to simple solutions even when the problems and causes are quite complex. Competitive pressure for superior returns pushes us towards short-sighted decisions such as we saw in the recent global financial debacle.

Or, does being blindsided come from flawed logic? Nassim Taleb, the author The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2007), argues just that. Taleb contends that most analytical models are built on past experience which is a bad guide to improbable yet high-impact events, precisely because they do not happen often.

My experience is that both causes are at play. In fact, they can reinforce each other. After studying financial arbitrage failures, David Stark from Columbia University offers evidence that trader’s analytical models and how they test their bets against other traders, locks them into a set of reinforcing relationship and logic orbits that can lead to disaster.

To minimize blind spots, leaders need constantly to test and stretch their relationships and logic boundaries. Here are some practical examples of how you can do this.

Objectives set the initial bar. Many advocate “stretch” objectives but what that means varies widely. Some organizations hold people firmly accountable to meet their stretch objectives. Under these conditions, people remove much of the stretch to increase certainty in reaching them. Managers respond by “cram down” where they reinsert the stretch. The ensuing negotiation evolves into a contest between the two as the quest for breakthrough results and thinking slides to the back burner.

Others use stretch objectives for aspiration. Don Dodge, former Microsoft startup evangelist now at Google, says that at Google it’s better to achieve 65% of the impossible than 100% of the ordinary. When he joined, he asked why set unrealistic goals? The response: “Because you can’t achieve amazing results by setting modest targets. We want amazing results.”

This approach places a greater burden on leaders. They have to keep fighting against incrementalism. They have to transform results assessment from a mechanistic comparison between actual and planned results to a more deliberative process. The advantage is this approach keeps everyone’s focus on doing astounding things rather than how accurately they hit their plan. (Granted, in areas such as operations where reliability trumps innovation, this approach might not apply.)

Once objectives are set, avoiding blind spots starts with expanding the inputs and assumptions one uses. As Taleb suggests, our experience becomes a filter that blocks considerations, particularly when they’re considered rare. Corporate cultures do the same thing in that they drive inclusion and bonding by excluding perspectives that differ. Conformity breeds blind spots.

Cultural boundaries are like water to a fish. They’re invisible and rarely discussed explicitly. Leaders unveil blind spots by heightening their awareness of alternatives. Research by Kathy Eisenhardt at Stanford describes fast decision makers as always having several contingency plans on hand based on different assumptions or outcomes.

Driving wider thinking starts with making today’s boundaries visible. Collectively, identify the time frame, market, cultural and technology assumptions that are embedded in current decisions. You’ll be surprised how much just increasing awareness of today’s boundaries triggers wider considerations.

Let’s turn to the logic used. Here are four provocative questions that I use to test the input and logic boundaries in any decision:

- What could happen that would make our current path go horribly wrong?

- If our major competitor were sitting here listening to us, what would delight them about the way we’re approaching this?

- If our most insightful customers were sitting here, what would their reaction be to our choice?

- If we were presenting this line of attack to a venture capitalist or buy-out firm, would they find it compelling?

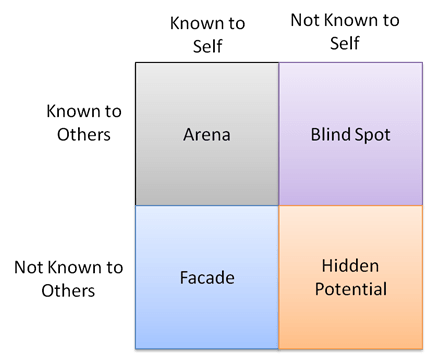

Years ago, Joe Luft and Harry Ingram created the famous Johari Window. Used to improve interpersonal relationships, they defined that which is not known to yourself or others as hidden potential.

Although most respond to my “what do you worry about…” referring to threats, blind spots also mask opportunities. Every so often an innovation comes around that makes you go “duh? Isn’t that obvious?” Think of wheels on suitcases. For years, nobody addressed what is now an expectation worldwide. We must have been blind.

I'm Christopher Meyer - author of Fast Cycle Time, Relentless Growth and several Harvard Business Review articles.

I'm Christopher Meyer - author of Fast Cycle Time, Relentless Growth and several Harvard Business Review articles.