Stress accentuates our most basic fears and predispositions. When Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein was asked what he’s learned about leadership during the recent financial crisis, he said, “I learned about the importance of making sure that everyone in the organization interprets his job or her job expansively…People can get trapped by their context.”

When we’re stuck in our personal context, we become defensive, self-serving, short sighted and simplistic. We react rather than create as our better aspirations give way to survival behavior. Stress accentuates our natural biases. Leaders know full well that getting people to look and reach beyond their local context is a constant challenge.

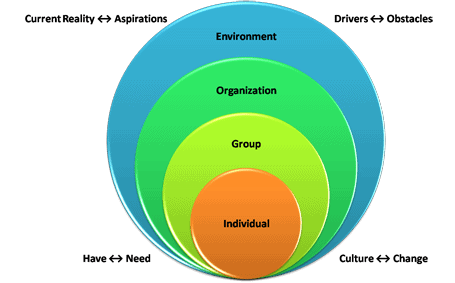

Here’s a simple model adapted from the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland that can help you encourage expansive thinking in yourself and others. The orbits represent the level of system from which one can view any situation starting with individual and eventually encompassing the total ecosystem. Narrow thinkers stay low and often stick within a single orbit. Expansive thinkers modulate up and down plus they can think across multiple orbits concurrently.

The four couplets that surround the circle represent tensions that shape our thinking and behavior in and between the orbits. Current reality represents today’s state versus aspirations for the future. Drivers and obstacles are those forces which motivate us move forward against the obstacles we encounter or expect. Have and need speak to the resources and capabilities on hand versus those required. Culture and change is a little bit different. Culture reflects one’s instinctive response whereas change reflects how well we adapt when our instinctive response doesn’t work as expected.

To illustrate the model, let’s look at a collaborative drug development effort between Genzyme and a smaller partner. What you’ll see is that like most of us, the context for project team members at both companies started at the individual orbit but stopped at the project (e.g. group in our model) particularly for Genzyme. It took some intervention outside the project to have the entire team expand their view.

For most of the Genzyme people, this collaboration was one of several projects they were assigned to whereas for their smaller partner, the collaboration was the only project on their plate. It was also the most important effort within the smaller company. The CEO of the smaller partner was constantly hovering over his people while Genzyme senior management delegated leadership to a program leader. Eventually, the pressure from the smaller firm’s CEO bled into the combined project team. Within the team, the smaller company members began pushing the Genzyme people harder. The Genzyme people became frustrated since they had other priorities to manage. The problem escalated beyond the project team to the point that the Genzyme executive who had established the partnership had to sit down with the smaller firm’s CEO to reset expectations. This was followed by meetings with individuals and the joint team to expand each one’s understanding of the other’s position and pressures. Together, a new set of operating guidelines were defined to re-align both groups.

For the smaller company project member, the distance between their orbits was tighter than at Genzyme because the project defined their company’s future as well as their individual and group destiny. Their aspirations, energy to attack obstacles, and resource demands from Genzyme were constantly growing and expressed more intensely. The starting context for Genzyme members rarely went beyond the group orbit. What was perceived by smaller company members as a major threat to their collective future was just one of many project issue to Genzyme members. When Genzyme’s asked for more robust clinical data from the smaller partner, it conflicted with their less mature systems and informal culture. Charges of “big company” bureaucracy and “small company naivety” flew back and forth.

In a retrospective analysis of the project conducted near project completion, all team members suggested that had they better known each other’s operating context, it would have significantly reduced frustration and wasted time. This would have helped them resolve the problems without escalation. With the luxury of 20-20 hindsight, it was clear that much of the tension was the result of narrow thinking.

Here is a pragmatic approach for using the framework:

- Identify the level of system from which you’re currently defining the opportunity or problem at hand

- Bump up or down one level and reframe the opportunity/problem from that perspective. Note how the tensions change.

- After doing the above yourself, test which orbit your collaborators are starting from and what they see when they shift to a new orbit. Note how the tensions shift.

- Optimize across the orbits recognizing that people participate at multiple levels of system simultaneously. There is no perfect context.

I'm Christopher Meyer - author of Fast Cycle Time, Relentless Growth and several Harvard Business Review articles.

I'm Christopher Meyer - author of Fast Cycle Time, Relentless Growth and several Harvard Business Review articles.

great post as usual!

What a great resource!

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any problems of plagorism

or copyright infringement? My website has a lot of unique content I’ve either created myself or outsourced

but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet

without my agreement. Do you know any techniques to help stop content from being ripped

off? I’d genuinely appreciate it.